Baobab Trees in Oman – an introduction to this natural wonder

If you travel to the southern reaches of Oman, especially near the monsoon‑‑influenced region of Dhofar, you may encounter a sight that seems more at home in African savannas than on the Arabian Peninsula: the mighty baobab tree. The term baobab trees in Oman captures this unexpected blend of geography and botany. These trees — often referred to as “up‑side‑down trees” because their bare branches resemble roots reaching towards the sky — stand as living monuments of endurance, adaptation and ecological richness. They’re not simply large trees; they carry stories of climate, culture and nature’s surprising versatility. From the moment you first glance at one, you sense both age and character: thick trunk, broad canopy, trunk sometimes hollowed, branches spreading wide.

In Oman the presence of baobab trees is relatively rare — yet their presence opens a doorway into a lesser‑known side of Oman’s natural heritage. For travellers, researchers, and locals alike, these trees represent a convergence of habitats: where monsoon‑influenced cloud‑forests meet arid landscapes, where African lineage plants find refuge on Arabian soil. In the sections to follow we’ll explore how these trees live, what makes them unique, where they are found, how they influence their surroundings, and how Oman is working to ensure their survival.

Natural habitat and regional setting of baobab trees in Oman

The baobab trees in Oman are concentrated primarily in the Dhofar Governorate, particularly in its wadis, escarpments and coastal zones where mist, humidity and unique micro‑climates occur. For example, it has been reported that Oman’s Dhofar region has about 200 baobab trees growing in small numbers near the wilayats of Dhalkut and Mirbat.

This concentration in Dhofar is no accident. The region receives a seasonal monsoon (known locally as the khareef) from June to September, which brings moisture and mist that sustains dry‑forest vegetation that you might not associate with Oman’s desert image. During that season the wadis and slopes become green, cool and humid, creating ideal conditions for plant species such as baobabs to survive where many others cannot. Wikiloc | Trails of the World+1

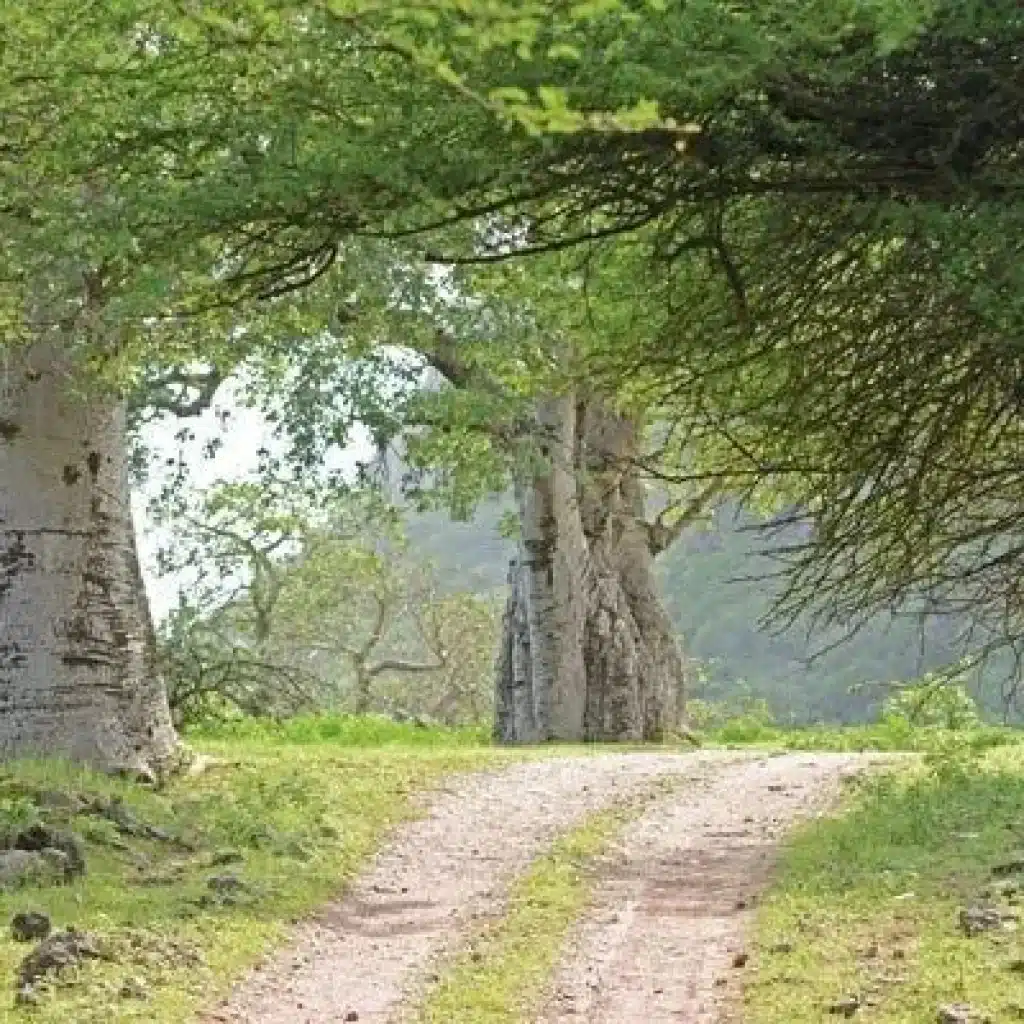

The trees are often found in coastal valleys or mountain slopes facing the Arabian Sea or Indian Ocean, in partnership with other rare plant species, under the cover of seasonal mist and monsoon influence. Some typical terrain where they grow includes Wadi Hanna east of Salalah, where a fine cluster of baobab trees can be found.

Thus, the habitat is somewhat niche: not deep desert, not lush rainforest, but a transitional and moderately humid zone where unique botanical processes occur. For visitors and scholars alike, this means that the location of the baobab trees in Oman is tied intimately to geography, climate and geology rather than simply random planting.

Origins and how the baobab came to Oman’s southern coast

When we ask “how did the baobab tree end up in Oman?” we encounter an interesting blend of botany, ecology and human history. The species in question is most commonly known as Adansonia digitata, the African baobab. According to botanical sources, while it is native primarily to the African continent, its presence in the Arabian Peninsula (including Yemen and Oman) is also recognised.

It is not entirely clear whether the baobab trees in Oman are truly indigenous (i.e., naturally occurring without human assistance) or whether they were introduced, perhaps via ancient trade connections along the Indian Ocean or via seeds carried by winds or birds. Some studies lean toward introduction, others suggest they may have naturalised over very long time frames. For instance a hiking trail record notes:

“Baobab trees are native to Africa, but they have been introduced to other parts of the world including Oman.” Wikiloc | Trails of the World

In either case, what is clear is that the trees have adapted to the local Oman‑Dhofar environment and survived for centuries (and perhaps millennia). Their presence is a botanical testimony of climate corridors, coastlines and biogeographical links between Africa and Arabia.

Moreover, local botanical research in Oman has documented their leaves, flowers and fruit and placed them in the context of Omani ecosystems.

In sum, the baobab trees in Oman are living relics: whether planted by ancient traders or naturally seeded, they now form a distinct part of Oman’s natural heritage, bridging continents and eras.

Botanical features of baobab trees: trunk, canopy, water storage

The baobab tree’s appearance is striking and memorable, and the specimens found in Oman share many of the features seen elsewhere — but also show adaptations to their local environment. Some of the key botanical traits include:

Massive trunk: Many baobab trees in Oman have trunk diameters approaching two metres and grow to heights of up to 15 metres. Gulf News+2Go Safari Salalah+2 The large girth of the trunk is a hallmark of mature baobabs.

Distinct shape: The branches often spread wide, creating a canopy that may resemble roots reaching toward the sky (giving rise to the “up‑side‑down tree” moniker). This silhouette catches the eye.

Water storage: One of the baobab’s most remarkable features is its ability to store water within its trunk and branches, enabling it to endure extended dry periods. According to general botanical literature, Adansonia digitata can store tens of thousands of litres of water.

Deciduous behaviour: Baobab trees typically lose their leaves during the dry season, regrow them when the rains or mist arrive. This helps reduce water loss and adapt to arid or semi‑arid conditions.

Flowers and fruit: In the Oman context, research shows that the leaves are palmate‑lobed, flowers large and creamy, and fruit similar to those found elsewhere in Africa.

In Oman, these features serve both the tree and the ecosystem: the large trunk acts as reservoir, the canopy provides shade and habitat, and the periodic leafing aligns with the seasonal climate of Dhofar. Thus, when you encounter a baobab tree during the monsoon‑influenced season, you’re seeing a tree that has evolved or at least adapted to survive in tough terrain.

Species and classification of the baobab found in Oman

The species most frequently referenced in Omán is Adansonia digitata, commonly called the African baobab. According to the Wikipedia entry for that species:

“The African baobab … is native to the African continent and the southern Arabian Peninsula (Yemen, Oman).” Wikipedia

In Omani botanical studies, this species is used when discussing the baobab trees of Dhofar. For example, a paper titled “Botany, Phytochemistry and Medicinal Benefits of Omani Baobab” treats the tree as the familiar baobab species but contextualised within Oman’s flora.

So, while there could potentially be local variants or subspecies, the main entity in Oman is the same baobab species found elsewhere in Africa. This reinforces both the uniqueness (rare in the region) and global connection of these trees.

From a botanical classification standpoint:

Family: Malvaceae (some older sources separate out into Bombacaceae)

Genus: Adansonia

Species: digitata

Thus in Oman when you hear “baobab tree”, you’re very likely dealing with this species. Understanding this helps in appreciating their ecology, age, growth rate and conservation needs.

Why Oman’s climate (especially in the Dhofar Governorate) supports baobabs

At first glance, Oman may seem an unlikely place for baobab trees — after all, much of the country is desert‑dry and arid. However, the Dhofar region enjoys a unique micro‑climate thanks to the south‑west monsoon (known as the khareef). From June through September, the region receives mist, moisture and cooler temperatures, which encourage vegetation thicker than typical desert flora. For the baobab trees, this climate offers more favourable conditions than most of Oman. For example:

The monsoon‑driven humidity and fog provide moisture during the otherwise dry time of year. According to a hiking trail write‑up:

“The mists of the Indian monsoon supply the area with humidity during the summer months, enabling a unique dry forest vegetation to grow.”

The terrain is often in valleys and wadis, where water collects and soils are more fertile than open desert.

The seasonal green period matches the leaf‑growth cycle of the baobab, enabling it to make use of the more favourable phase to photosynthesise and grow.

In sum, the combination of coastal slope, monsoon influence and sheltered valleys creates a niche in which baobab trees can establish and persist. Without these special conditions, their survival in Oman would be far less likely. Thus, they are somewhat of a climatic anomaly — trees normally associated with African savannas now thriving (though in small numbers) in southern Oman.

Ecological role of baobab trees in Oman’s ecosystems

Within their habitat, baobab trees perform several essential ecological roles — even though they are relatively rare in Oman. Some of these roles include:

Habitat provision: The large canopy and trunk of a baobab provide shelter for birds, insects and small mammals. In a region where large trees may be few and far between, these giants stand out as vertical structure in the landscape.

Water regulation: Because they store water within their trunk and branches, baobabs can act as micro‑reservoirs of sorts, moderating local humidity and offering resilience in dry periods.

Soil stability and nutrient cycling: The fallen leaves and branches of baobab trees contribute organic matter to soils over time. In the Dhofar environment, where soil may otherwise be shallow or rocky, this is valuable.

Biodiversity support: The presence of such trees supports a small but significant diversity of flora and fauna that might specialise in the micro‑habitat around them – for instance, mosses, lianas, certain birds and insects that prefer large‑tree cover in the monsoon‑fog zone.

Ecological legacy: Because some of these trees are centuries old, they form part of the long‑term ecological memory of the region. Their trunks may bear hollows, their seeds travel, and they provide continuity across generations of flora and fauna.

In Oman’s Dhofar region, the baobab trees add both ecological value and aesthetic value — drawing tourists, researchers and local nature‑enthusiasts — thereby providing impetus for conservation and awareness.

Cultural significance: local traditions, folklore tied to baobabs

Though baobab trees in Oman are numerically small compared to their home ranges in Africa, they nonetheless carry cultural weight. Locals in Dhofar often regard them as remarkable trees — symbols of endurance, age and botanical rarity. For example:

Local tour guides often reference their African origins and the extraordinary sight of such trees in Oman.

The sheer age of some trees (hundreds of years) gives them a kind of sacred or storied status; people may pause in their presence, photograph them, or include them in nature walks.

Whilst detailed folklore specifically tied to Omani baobabs may be fewer than in Africa, the general concept of the baobab as a “tree of life” or a giant survivor resonates with a wider cultural appreciation of trees in arid lands.

Moreover, the tourism narratives around the baobabs lean into their cultural novelty: foreign visitors see them as exotic, local guides frame them as part of Oman’s natural heritage, and communities increasingly recognise them as assets worth protecting. This cultural significance supports family‑friendly nature walks, eco‑tourism, and educational programmes.

Tourism appeal: visiting baobab trees in Oman, photography, nature walks

For travellers to Oman — especially the Dhofar region — the baobab trees present a unique attraction: they are both rare and visually striking. Tourism programmes emphasise the baobabs along with other natural features of Dhofar, like the monsoon‑green hills, coastal cliffs and wadis. Some useful points for visitors include:

The trees are especially photogenic during the khareef season (June to September) when mist and greenery surround them, enhancing their dramatic silhouette.

Some tour operators mention that the drive from Salalah to the baobab tree sites (for example near Mirbat) offers scenic landscapes, giving tourists a dual experience of terrain and tree.

Local tips for visiting: go early or later in the day for good light and fewer crowds; wear sturdy shoes if exploring wadis; bring water and snack since facilities may be limited.

From a photography perspective: the contrast of the massive trunk against the sky, the monsoon‑mist backdrop, and the surrounding terrain create memorable frames.

For nature walks: tracking trails near Wadi Hanna or Ayn Shawny stream offer combined hiking

Thus, for the visitor who has seen Oman’s deserts and beaches, the baobab trees add an unexpected botanical highlight — one that blends nature, adventure and aesthetics.

Key locations in Oman where baobab trees grow naturally

While the baobab trees in Oman are not extremely widespread, they appear in specific, identified zones. Among the key locations:

Wilayat of Dhalkut in Dhofar Governorate.

Wilayat of Mirbat (particularly around the plain of Hasheer) where conservation efforts are being focused.

Wadi Hanna (east of Salalah) where a cluster of baobab trees can be experienced along with nature trails.

Other wadis like those near Ayn Shawny stream, where GPS‑mapped hikes show baobab‑tree presence

If you are planning a visit, it is wise to combine the baobab tree stop with other attractions in Dhofar (coastline, wadis, monsoon‑hills) to make the trip richer. Local visitors recommend a rental car or guided tour, as many of these sites are remote and not heavily signposted.

The region of Dhalkut and Mirbat: hotspots for baobab populations

Focusing in on two zones: Dhalkut and Mirbat stand out as hotspots for the baobab trees in Oman. In Dhalkut, trees are documented and surveyed for conservation. In Mirbat, the local authorities plan to establish a park specifically for the baobab trees. For example:

The article “Rare, giant baobab trees in Oman under protection” notes that Dhofar region has around 200 baobab trees in these key areas.

In December 2024 the Environment Authority (Oman) launched a campaign in Dhofar to plant 160 baobab trees to establish the first environmental park for baobab trees at Hasheer Plain near Mirbat.

These hotspots matter for several reasons: they concentrate the few baobabs in viable habitats, they provide manageable destinations for tourism, and they serve as conservation centres where monitoring, planting and protection efforts are active. For visitors and researchers alike, focusing on Dhalkut and Mirbat offers the best chance of seeing baobab trees in Oman in a natural (or semi‑natural) state.

Biodiversity around the baobab trees: fauna and flora associations

Although the baobab trees are the icon, the ecosystem around them is equally interesting. Because they grow in monsoon‑influenced dry‑forest zones, a rich assemblage of plants and animals is often present. Some ecological notes:

The surrounding vegetation may include other rare plants that thrive in the misty, coastal slopes of Dhofar. The low tree‑forest cover in such regions creates niches for a variety of species.

The large canopy of a baobab may host birds, insects and possibly bats (since in Africa some baobabs are pollinated by fruit‑bats). While specific studies in Oman may be fewer, the botanical paper on Omani baobabs mentions the flower biology, which suggests large night‑blooming flowers

The presence of these trees adds structural diversity to the landscape, which in turn supports different micro‑habitats (shade, leaf litter, trunk hollows).

Environmental threats to this biodiversity include grazing, human disturbance, pests and climate shifts. The fact that a monitoring campaign was launched for pests and insects affecting baobab trees in Oman underlines the interconnectedness of tree health and broader biodiversity health.

So, when visiting the baobab tree areas, it’s beneficial to consider not only the trees themselves but also the network of life around them — birds, shrubs, the soil community, and even the seasonal monsoon dynamics.

Historical relevance: maritime trade, ancient habitats and the baobab

The presence of baobab trees in Oman invites reflection on ancient geographies. The southern coast of Oman was part of long‑distance maritime trade routes across the Indian Ocean, connecting Africa, Arabia and South Asia. It is plausible that early travellers, seafarers, traders or even drifting seeds brought baobabs to Oman’s shores. Though direct records are limited, the botanical and ecological evidence supports the idea of long‑term presence.

In addition, Oman’s natural history includes forest types, wadis and valleys that were more vegetated in past centuries than the fully arid zones today. The baobab trees may be remnants of older, wetter landscapes or adaptations to micro‑climates that persisted despite regional aridity elsewhere. Thus, each baobab tree in Oman is a living link between the present and deep ecological history.

Moreover, the fact that Oman is now establishing parks and research efforts for baobabs implies recognition of their heritage value. They are not just trees, but symbols of landscape continuity and change over time.

Traditional uses of the baobab tree in Oman (food, shelter, craft)

While much of the popular use of baobab trees is documented in Africa, in Oman there are still studies that examine their traditional uses. For example, the journal article on Omani baobab notes phytochemical and medicinal properties, pointing to local usage of leaves, flowers and fruit.

Some of the uses include:

Leaf and seed products: The leaves of baobab trees are rich in certain nutrients and may have been used in local herbal preparations.

Fruit pulp: In Africa the baobab fruit pulp is edible and considered nutritious; while the Oman usage is less documented, the same species suggests similar potential.

Shelter and materials: Large trees provide shade and may serve as gathering points or landmarks. Locals may tie cultural significance or utilise parts of the tree in informal ways (even if less formally recorded).

Ecotourism and educational use: More recently the baobab trees serve as focal points for nature walks, interpretation and tourism‑driven livelihoods, which is itself a kind of use — i.e., sustainable nature‑based use rather than traditional.

Given their rarity in Oman, the uses here may lean more toward appreciation and conservation rather than heavy exploitation — which in turn helps preserve their value.

Medicinal and health aspects of baobab trees in Oman

The article titled “Botany, Phytochemistry and Medicinal Benefits of Omani Baobab” provides a substantive look at the leaf morphology, flower biology and potential health benefits of the baobab in Oman.

Key points from that research include:

Leaves: Palmate with 5‑7 lobes, bright green, and emerging after the rainy season.

Flowers: Large, white or cream‑coloured, with long slender petals, often nocturnal in bloom and pollinated by bats or insects.

Fruit/seed: Similar in nature to African baobabs — thick‑shelled fruit containing pulp that may have nutritional value.

Phytochemical studies: The paper explores compounds in the baobab leaf and fruit that may have antioxidant, anti‑inflammatory or nutritional properties (though detailed human‑clinical data for Oman may be limited).

For residents or visitors interested in natural health, the baobab tree offers a case study of how a tree from Africa, transplanted into or naturalised in Oman, still retains valuable plant‑chemistry attributes. However, it’s important to note that any medicinal use should be approached with appropriate guidance and local regulation, especially given conservation concerns.

Conservation efforts: protecting these rare baobab trees in Oman

Because the baobab trees in Oman are relatively rare (estimates suggest around 200 individuals in key zones) and face threats from pests, climate stress and human disturbance, there are now active conservation programmes. Some of the notable efforts include:

The Environment Authority in Dhofar launched a campaign in December 2024 to plant 160 baobab trees to establish a dedicated baobab tree park at Hasheer Plain near Mirbat.

Earlier, monitoring campaigns were launched to protect existing trees from harmful pests like the leg borer bug. The Dhofar‑Environment Directorate reported surveys and budgets for the extraction of insects and trunk treatment.

Nurseries: Seeds have been collected, prepared in nurseries, then transplanted to the park site, indicating a propagation strategy rather than simply passive protection.

These efforts show that Oman is not only recognising baobab trees as natural heritage but is taking steps to secure their future. For visitors and locals, this means that awareness, responsible tourism and support of local conservation initiatives can make a real difference.

Environmental challenges and threats to baobab populations in Oman

Despite the conservation efforts, baobab trees in Oman face multiple challenges:

Pests and insects: As noted, insect infestation (such as leg borer bug) threatens the health of these trees.

Climate stress: While Dhofar enjoys monsoon fog, overall the environment is still arid and sensitive to changes. Climate change may reduce mist frequency, increase drought stress, or alter the delicate micro‑climate that baobabs rely on.

Limited numbers: With only a few hundred individuals, genetic diversity may be low, and any loss is proportionally significant.

Human disturbance: Tourism, uncontrolled grazing, vehicle access and habitat alteration can damage root systems, soil compaction, and overall tree health.

Introduction/competition: Invasive species or changes in land use can alter the ecosystem balance, making it harder for baobabs to thrive.

Addressing these challenges requires ongoing monitoring, community education, careful land‑use policy and sustainable tourism practices.

Community involvement: local initiatives and awareness campaigns

Community involvement is vital for the long‑term survival of baobab trees in Oman. Some ways in which local communities and organisations are participating:

Volunteer teams in Dhofar work with the Environment Directorate to monitor tree health and extract pests.

Tour operators and guides incorporate baobab‑tree visits into educational tours, raising awareness among tourists about their significance.

Schools and eco‑education programmes increasingly include the baobab as an example of natural heritage, emphasising its rarity and value.

The planting of new trees under the park initiative offers local job/volunteer opportunities, as seeds are collected, nurseries managed and saplings planted.

Such involvement is not just good for the trees—it fosters a sense of ownership and pride among local residents, which often means better protection and stewardship.

Botanical research and studies on Oman’s baobab trees

A growing body of research is focussing on the baobab trees in Oman. The aforementioned study on botany, phytochemistry and medicinal benefits is one example.

Other research activities include:

Inventories of tree populations, including age estimates, trunk diameter, health assessments (for example via monitoring pests).

Ecological mapping of where baobabs occur relative to monsoon‑fog zones, geology and terrain.

Studies of the tree’s leaf phenology (timing of leaf flush and drop) in Oman’s specific climate regime. The Oman Observer article notes that some baobab trees mature their leaves for only three months in fall in Dhofar.

Plant physiology research: understanding how these trees survive water stress, store moisture and adapt to arid conditions.

For academics, students or citizen‑scientists in Oman, the baobab offers a promising subject: rare, regionally unique and linked with broader themes of climate adaptation, biogeography and conservation.

Photography and experiential tips: capturing baobab trees in Oman

If you plan to visit the baobab trees in Oman, here are some practical and photographic tips:

Best time of day: Early morning or late afternoon provides soft light and fewer harsh shadows. During khareef season, mist can add atmosphere.

Umístění: Sites like Wadi Hanna – ensure you have good footwear and allow for some walking off the main road.

Composition: Include the full trunk plus canopy to show scale. Use the surrounding landscape (wadi, mountain slope, mist) as context.

Perspective: Photograph from below to emphasise the height and girth of the tree; consider including a person for scale.

Seasonal context: The green surroundings during khareef complement the tree; outside of that period the contrast of tree against drier landscape offers a different aesthetic.

Respect nature: Stay on trails, avoid damaging roots or bark, minimise noise and litter – this helps maintain the site’s condition.

Gear: Bring a wide‑angle lens for the full tree + landscape, and perhaps a telephoto if you want to capture details of branches or local birds/insects.

Documentation: If you’re into citizen science, you might photograph bark health, trunk diameter, leafing status — this can help conservation efforts.

These tips will help you not just “see the baobab trees in Oman” but experience them deeply and responsibly.

Eco‑tourism and sustainable travel centred on baobabs in Oman

The baobab trees in Oman provide an excellent opportunity for eco‑tourism – travel that is nature‑based, culturally respectful and conservation‑minded. Some considerations for sustainable travel:

Local guides: Support local tour operators in Dhofar who include the baobab tree sites and ensure that they provide interpretation (ecology, culture, conservation) rather than just a photo stop.

Small group tours: Limit impact by going with smaller groups; avoid overwhelming the site which is still ecologically sensitive.

Off‑peak season: While the khareef season is visually magnificent, visiting outside peak times may mean fewer crowds and more intimate experiences — though ensure safety and access are good.

Responsible behaviour: Stay on marked paths, respect signage, avoid carving into trunks or disturbing roots.

Educate and share: Use your visit to raise awareness — social media posts, blogs, or conversations that highlight the rarity and significance of these trees help their cause.

Offset travel impact: Consider contributing to local tree‑planting efforts (some initiatives exist for baobab replanting) or engage with local conservation NGOs.

By integrating these practices, your visit becomes not just about seeing a tree, but about participating in its stewardship.

Myths and misconceptions about baobab trees in Oman

As with many “iconic” tree species, the baobab trees in Oman are subject to a few myths and misunderstandings. Some clarifications:

Myth: “These trees are thousands of years old and thus immortal.”

Reality: Some baobabs may be centuries old, but they are not immortal. They face biological stress, pests and climate impacts. In Africa large baobabs have died unexpectedly in recent years.Myth: “They naturally grew everywhere in Oman.”

Reality: Their presence is very limited and tied to specific niche habitats in Dhofar. They are not broadly spread across Oman’s deserts.Myth: “They require lots of rain like a rainforest tree.”

Reality: Baobabs are adapted to dry and semi‑dry climates; the key in Oman is the seasonal mist and monsoon‑related humidity, not heavy rainfall year‑round.Myth: “They can be planted easily and will thrive anywhere in Oman.”

Reality: Propagation is possible (as conservation efforts show) but establishing mature baobabs requires right site, climate and care. Some tree parks are now being developed to support this.

Recognising these points helps provide a realistic and respectful view of the baobab trees in Oman rather than romantic exaggeration.

Impact of climate change on baobab trees in Oman

Climate change poses a real but complex challenge for baobab trees in Oman. Some points to consider:

The monsoon fog‑and‑mist regime that supports Dhofar’s vegetation may alter in frequency or intensity due to warming seas or changing atmospheric flows. If mist seasons reduce, trees like the baobab may get less moisture than they’ve adapted to.

Heightened temperatures, increased drought length or more erratic rainfall could stress trees, making them more vulnerable to pests or dieback.

On the positive side, the presence of such trees in a marginal habitat means they could serve as indicators of ecological change: shifts in their health may signal broader ecosystem stress.

Conservation and planting efforts (such as the baobab tree park) help build resilience by increasing numbers, genetic diversity and creating more optimal micro‑habitats.

Thus, while the baobab trees in Oman are resilient, they are not immune. Climate change adds urgency to their protection and underscores the value of preserving their ecosystems.

Educational value: what baobab trees in Oman teach us about nature

Baobab trees in Oman are more than tourist attractions; they’re living teachers. They offer several important lessons:

Adaptation: They show how species normally associated with Africa can adapt to a new environment when the conditions (micro‑climate, soil, mist) align.

Resilience: Living for centuries in semi‑arid zones teaches us about long‑term survival strategies: water‑storage, deciduous behaviour, thick trunks.

Connectivity: Their presence indicates historical connections (botanical, climatic, geographic) between Africa and Arabia, reminding us of the fluidity of nature.

Conservation: They highlight the value of protecting rare species in limited numbers: small populations can still matter globally.

Sustainable tourism: Their role in nature‑based tourism shows how natural heritage can support local economies if handled responsibly.

Climate signals: They serve as biological indicators: changes in their health may reflect shifts in local climate or habitat conditions.

Educators, nature guides and conservationists can use the baobab trees in Oman as case‑studies in sustainability, ecology and heritage.

The future outlook: what lies ahead for baobab trees in Oman

So, what does the future hold for baobab trees in Oman? A few forward‑looking thoughts:

Thanks to planting efforts (such as the tree‑park near Mirbat) and monitoring programmes, there is a foundation for increased baobab populations and genetic safeguarding.

If eco‑tourism remains sensitive and educational, then the trees may find increased protection through the value placed on them by visitors and locals alike.

Research will likely expand: deeper studies into age, genetics, adaptation and ecological interactions may emerge, enabling better conservation strategies.

The main risks will be climate change, human disturbance and resource pressures; careful land‑use planning, grazing management and visitor control will be key.

Over the next decades, baobab trees in Oman could become emblematic of Dhofar’s natural heritage — much like the frankincense trees or dragon trees are in other parts of the peninsula.

In short, while the future is not guaranteed, the prospects are positive — if supported by conscious action. The baobab trees in Oman, though few, hold outsized significance and can continue to stand tall if we choose to value and protect them.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the baobab trees in Oman commonly called?

They are commonly referred to simply as “baobab trees”, though locally you might hear Arabic references to “tree of life” or “up‑side‑down tree”. In scientific terms they are often the species Adansonia digitata.

How many baobab trees exist in Oman?

Estimates suggest around 200 trees in the Dhofar region in key locales such as Dhalkut and Mirbat.

Can you visit the baobab trees in Oman easily?

Yes — there are accessible sites near Salalah, for example Wadi Hanna or the coast near Mirbat. Some tour operators will offer guided excursions.

Are the baobab trees native to Oman or were they introduced?

The scientific consensus is that Adansonia digitata is native to Africa, and its presence in Oman may be naturalised or introduced long ago.

What is being done to protect the baobab trees in Oman?

Conservation efforts include monitoring for pests, planting new trees (e.g., the park near Mirbat with 160 new baobabs), collecting seeds, establishing nurseries and raising public awareness.

When is the best time to visit to see baobab trees in their full splendour?

During the khareef (monsoon) season from June to September in Dhofar is ideal, when mist, greenery and moisture enhance the setting. However, other times of year offer less humidity but perhaps clearer skies and fewer visitors.

Závěr

The baobab trees in Oman are remarkable in many ways. They bridge continents, climates and centuries. They bring to the Arabian Peninsula a sense of botanical wonder more commonly associated with African landscapes. In Oman’s Dhofar region, amidst mist‑clad slopes and green‑washed valleys during the monsoon, these trees stand as silent sentinels of nature’s adaptability and endurance.

Yet they are rare and fragile. With only a couple of hundred documented specimens, each tree matters. Their conservation is not just a botanical footnote but a key part of Oman’s natural heritage. For tourists, they offer a unique attraction; for locals, a natural treasure; for scientists, windows into adaptation and resilience.

By visiting respectfully, supporting local conservation, learning about their ecology and sharing their story, we can help ensure that the baobab trees in Oman are not merely curiosities but living legacies — roots in the past, branches into the future.

Komentáře (0)